#randy lofficier

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Batman: Nosferatu

by Randy Lofficier, Jean-Marc Lofficier, and Ted McKeever

#comics#comic books#art#illustration#panelswithoutpeople#graphic novel#graphic novels#dc#dc comics#dc elseworlds#batman#nosferatu#batman: nosferatu#randy lofficier#jean-marc lofficier#ted mckeever#bat signal#batsignal#german expressionism#carl mayer#hans janowitz

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cheetah from WONDER WOMAN: THE BLUE AMAZON (2003)

#Cheetah#Wonder Woman#DC Comics#The Blue Amazon#Ted McKeever#Randy Lofficier#Jean-Marc Lofficier#2003#Elseworlds

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frank Frazetta-Fantasy Illustrated #7: Phantom of Which Opera

by Randy Lofficier; Jean-Marc Lofficie and Timothy II

Quantum Cat Entertainment

#quantum cat entertainment#Frank Frazetta-Fantasy Illustrated#comics#anthology#timothy II#Jean-Marc Lofficier#Randy Lofficier

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alone in the Dark #1 (July 2002) by Image Comics

Written by Randy Lofficier and Jean-Marc Lofficier, drawn by Matt Haley, Aleksi Briclot and David Hahn.

#Alone in the Dark#2002#Image Comics#Etsy#Vintage Comics#Comic Books#Comics#Randy Lofficier#Jean-Marc Lofficier#Matt Haley#Aleksi Briclot#David Hahn#Adaptation#Video Games#Gaming

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Free to Borrow Books about Tintin and Hergé

The only requirement is to make an Internet Archive account. (If you already have an account, check if it was compromised in the recent hack and change your password.) Note that this is in no way a comprehensive list of works or an ideal Tintinology primer, just the books that have been made available on the archive, which also means that it contains everything from picture books to highly academic texts. However, I've marked with a * the books I think are best to start with.

Includes works in both English and French (plus a few in Spanish). Please don't hesitate to ask if you have questions!

General reference

Tintin and the world of Hergé Benoît Peeters, 1989*

Tintin, Hergé and his creation Harry Thompson, 1991

Tintin: The Complete Companion Michael Farr, 2001*

The Pocket Essential Tintin (1st ed.) / (2nd ed.) Jean-Marc & Randy Lofficier, 2002 / 2007

Les mystères du Lotus Bleu Pierre Fresnault-Desruelle, 2006

Captain Haddock Thompson and Thomson Professor Calculus Rastapopoulos (FR) Tchang (FR) Michael Farr, 2007

Figurines Tintin: La Collection Officielle Daniel Couvreur, Frédéric Soumois, & Dominique Maricq, 2012-2015

Hergé Dada magazine, 2016

Catalogues

Hergé, 1922-1932 : les debuts d'un illustrateur ed. Benoît Peeters, 1987

Hergé dessinateur ed. Pierre Sterckx & Benoît Peeters, 1988

The adventures of Tintin at sea Yves Horeau, 2004

Musée Hergé / Tintin : the art of Hergé Michel Daubert, 2013*

L'univers du createur de Tintin Artcurial, 2023

Biography

Hergé : portrait biographique Thierry Smolderen & Pierre Sterckx, 1988

Entretiens avec Hergé / Conversations with Hergé (excerpts) Numa Sadoul, 1989*

Hergé / Hergé: The Man Who Created Tintin (abridged translation) Pierre Assouline, 1996

Les Aventures d'Hergé / The Adventures of Hergé Jean-Luc Fromental, José-Louis Bocquet, & Stanislas, 1999

Hergé, fils de Tintin / Hergé, son of Tintin Benoît Peeters, 2002

The adventures of Hergé, creator of Tintin Michael Farr, 2007

Hergé: lignes de vie Philippe Goddin, 2007

Analysis

Le Monde de Tintin Pol Vandromme, 1959

Tintin chez le psychanalyste Serge Tisseron, 1985

Hergé écrivain Jan Baetens, 1989

L’archipel Tintin A. Algoud, J.-M. Apostolidès, D. Cerbelaud, B. Peeters, P. Sterckx, 2003

Tintin and the secret of literature Tom McCarthy, 2008

Les Secrets d'Hergé dessinateur Bruno Cassiers, 2022

Fiction & Novelizations

Ma vie de chien Ariane Valadié, 1994

Tintin in the new world / Tintin en el nuevo mundo François Tuten, 1996

La vie cachée de Tintin Henri Roanne-Rosenblatt, 2005

Petit dictionnaire énervé de Tintin Albert Algoud, 2010

The Adventures of Tintin: a novel / Les Aventures de Tintin: le roman du film / Las aventuras de Tintín Alex Irvine, 2011

The adventures of Tintin : the chapter book (print disability borrow only) / Les aventures de Tintin: l'album du film Stephanie Peters, 2011

Tintin's daring escape / Les évadés du Karaboudjan / Fuga temeraria Danger at sea / Peligro en el mar The mystery of the missing wallets Kirsten Mayer, 2011

Trivia

Êtes-vous tintinologue? François Hébert, 1983

Tintin and Snowy Big Activity Book Guy Harvey & Simon Beecroft, 2006

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

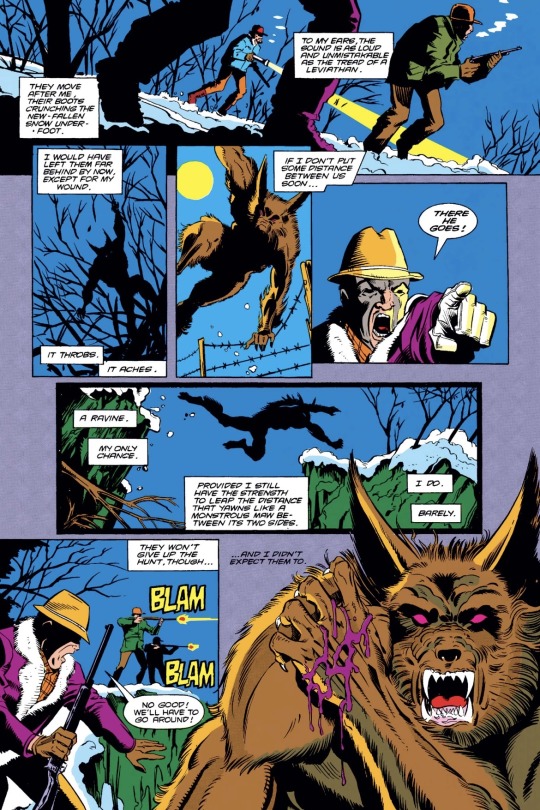

TOPAZ & JACK RUSSELL in DOCTOR STRANGE, SORCERER SUPREME (1988) #27 by DANN THOMAS, JEAN-MARC LOFFICIER, RANDY LOFFICIER, and ROY THOMAS

#doctor strange#werewolf by night#jack russell#topaz#marvel#marvel comics#stephen strange#wbn#wwbn#comics#cowboy barbie topaz my beloved

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

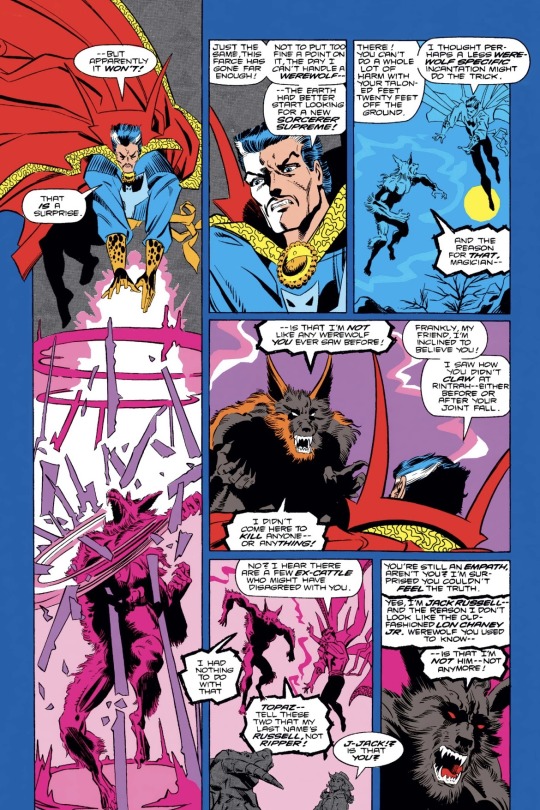

Action Comics #579, in which Keith Giffin and Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier sent Superman back in time to fight Asterix and Obelix.

There was a few months after the Crisis but before the Post-Crisis when you could get away with anything.

#superman#dc#asterix and obelix#clark kent#Ils sont fous ces kryptonies#Keith Giffin#you madman what have you done

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Continuing to promote my work...

"The Vampire and the Air Pirate" (included in THE LAST TALES OF THE SHADOWMEN 20: FIN DE SIECLE, Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier, eds., Black Coat Press, 2023)

The Last Tales of the Shadowmen 20: Fin de Siecle

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reinterpreting the Justice League as Retro Horror and Sci-Fi Films

Inspiration taken from Randy and Jean-Marc Lofficier’s trilogy of German Expressionist Elseworlds stories and Dan Abnett and Andy Lanning’s The Superman Monster.

The Dark Night (1939): On an evening in Victorian England, a man is fished out of a river, laughing uncontrollably and gibbering to himself about an enormous bat and the coming of night. He is taken to the Arkham Psychiatric Institute, and the next morning it is discovered that he has complete amnesia and cannot remember any details of his past, nor what his ravings the previous evening meant.

When a wealthy gentleman who is interested in financing the institute visits, the patient begins to have terrible nightmares and hear voices whispering to him from the dark. Soon, orphan children around London begin to go missing, and the patient realizes this wealthy gentleman is, in fact, a vampire. He desperately tries to inform the doctors, but they dismiss him, all while the patient struggles with his mental anguish and resisting the compulsion to join the vampire’s dark crusade.

The day is the his only refuge, until children begin visiting him to laugh at and mock him. He realizes these are thralls of the vampire that he sends to further his agenda during daylight hours, and over the coming weeks his health deteriorates as he lapses back into his half-nervous, half-euphoric laughing tic. Finally, when he can bear it no longer, he resolves to break out of the asylum and kill the vampire himself. The movie ends with ambiguity over whether the man really was a vampire or if the patient was experiencing delusions.

Übermensch (1938): In a quest to create the next stage of our evolution, Dr. Alexander Luther goes to cemeteries around the continent to steal body parts from the most physically and mentally fit humans Europe has ever known. Finally, he returns to his hometown’s church, Our Lady of Mercy, to excavate the body of a beloved friend who died in boyhood.

After digging up the Mercy graves, he removes his friend’s heart and implants it into his creation’s chest before bringing it to life. Luther rejoices at his scientific accomplishment, before realizing that the creature’s sense of morality is completely alien, and it puts no value on human life. Seeing that he has created a monster, Luther vows to destroy it.

Though he designed the Übermensch to be indestructible, he ultimately defeats it by appealing to the memories of innocence and virtue left in his childhood friend’s heart. While the creature has its guard down, he then pushes it into the frigid waters of the arctic, encasing it in ice forevermore.

Wolf Woman (1941): When her estranged father dies, heiress Minerva Rich travels to his home in Greece to have his will sorted out. Shortly after they arrive, a spate of attacks attributed to a large dog occur, but Rich thinks nothing of it until the night she is walking home and is accosted by an enormous lupine beast. No one believes her account until she brings the story to the secretary of her father’s lawyer, whom she has befriended.

At the secretary’s recommendation, Minerva goes to Circe, a mysterious woman living on the outskirts of town who tells her the legend of the werewolf— how when the Greek gods were displeased with someone, they would curse them to transform into a terrible beast by the light of the moon*.

Circe then opens a tome and tells Minerva of an Ancient Greek queen who was barren and begged the gods for a child. The gods agreed, on the condition that on the girl’s eighteenth birthday, she be given up to them. But when the child’s birthday came, her mother refused to let her go, and the gods forcibly took the girl, telling her mother that the child would become an unstoppable warrior, feared by all… but at a terrible price. Since then, the princess has wandered Greece as a werewolf.

Circe gives Minerva an amulet of a cat’s head and says she can help her defeat the wolf, but just like with the gods, all gifts come at a cost. Minerva begins noticing strange feelings of rage and physical changes in the coming nights, until the film’s climax, when she transforms into a panther-woman. Her and the werewolf have a dreadful fight that ends with Minerva piercing the wolf’s heart when both are caught in a snare trap set by the townspeople. As the sun rises, the werewolf transforms into Minerva’s secretary friend and rapidly ages before crumbling into dust in front of her very eyes.

*This isn’t really accurate. I’m going for the old horror trope of “Yeah, it’s an ancient legend that dates all the way back to a week ago when we were in the writer’s room.”

#roll the bones#bones’ writing#batman#the joker#superman#lex luthor#wonder woman#the cheetah dc comics#circe dc comics#dc comics#classic horror#vampires#werewolves#frankenstein#i have many more after these three#but those can wait#dracula#the wolf man#classic monsters#horror

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robur: Eine moderne Hommage an Jules Verne und H.G. Wells "Robur" ist ein Comic, geschrieben von Randy Lofficier und Jean-Marc Lofficier und illustriert von Gil Formosa. Diese Serie basiert lose auf der Figur Robur aus Jules Vernes Roman "Robur der Eroberer" und entführt ihn in neue, aufregende Abenteuer. Die Comic-Trilogie umfasst drei Bände: Band 1: "De la Lune à la Terre" (Von der Mond zur Erde) In diesem Band wird die Erde von den Seleniten, einer Mondrasse aus H.G. Wells' Romanen, erobert. Robur der Eroberer führt die menschliche Widerstandsbewegung gegen die Invasoren an. Dieser Band kombiniert Science-Fiction-Elemente mit einer alternativen Geschichtsschreibung, die Robur als zentralen Helden darstellt. Band 2: "20.000 Ans sous les Mers" (20.000 Jahre unter den Meeren) Der zweite Band vertieft die Geschichte, indem er die Leser in die Tiefen der Ozeane führt. Robur kämpft weiterhin gegen die Seleniten und nutzt dabei fortschrittliche Unterwassertechnologien. Dieser Band ist eine Hommage an Jules Vernes "20.000 Meilen unter dem Meer" und erweitert das Universum von Robur um maritime Abenteuer. Band 3: "Voyage au Centre de la Lune" (Reise zum Zentrum des Mondes) Im finalen Band der Trilogie führt Robur eine Expedition zum Mond, um das Herz der Invasion zu zerstören und die Erde zu befreien. Dieser Band verbindet Elemente aus H.G. Wells' und Jules Vernes Werken und liefert einen spannenden Abschluss der Serie. Illustrationen und visuelle Gestaltung Die Illustrationen von Gil Formosa sind detailreich und dynamisch, was die epischen Abenteuer von Robur zum Leben erweckt. Formosas Kunstwerk fängt die atmosphärische und abenteuerliche Stimmung der Serie perfekt ein und trägt maßgeblich zur Faszination der Geschichten bei. Veröffentlichung und Rezeption Die Serie wurde ursprünglich im französischen Verlag Albin Michel veröffentlicht und erschien später in englischer Sprache im Heavy Metal Magazin. Die "Robur"-Serie ist ein faszinierendes Beispiel für moderne Adaptionen klassischer Literaturfiguren und bietet eine Mischung aus Science-Fiction, Abenteuer und alternativer Geschichte, die Fans beider Genres begeistern wird. Fazit "Robur" von Randy Lofficier, Jean-Marc Lofficier und Gil Formosa ist eine beeindruckende Comic-Serie, die die klassischen Werke von Jules Verne und H.G. Wells aufgreift und in ein modernes, spannendes Format bringt. Mit detailreichen Illustrationen und einer packenden Handlung bietet diese Serie eine faszinierende Reise durch alternative Welten und epische Abenteuer.

0 notes

Text

Batman: Nosferatu

by Randy Lofficier, Jean-Marc Lofficier, and Ted McKeever

#comics#comic books#art#illustration#panelswithoutpeople#graphic novel#graphic novels#batman#batman nosferatu#batman: nosferatu#nosferatu#randy lofficier#jean-marc lofficier#ted mckeever#dc#dc comics#dc elseworlds#german expressionism#gotham city#arkham asylum#metropolis

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

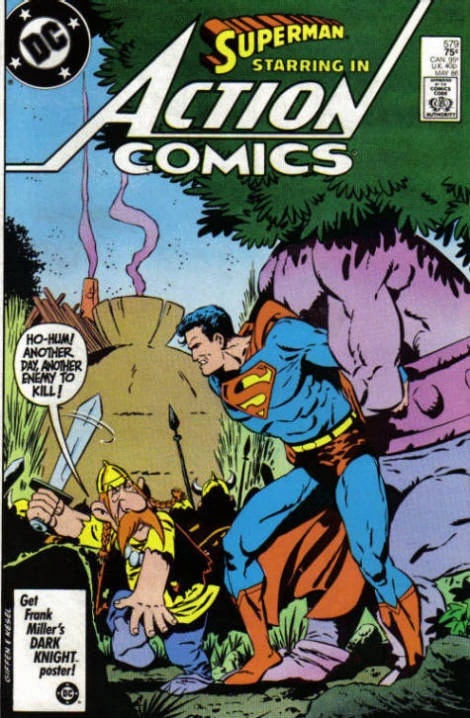

Map from Moebius' Arzach novel by Jean-Marc & Randy Lofficier.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

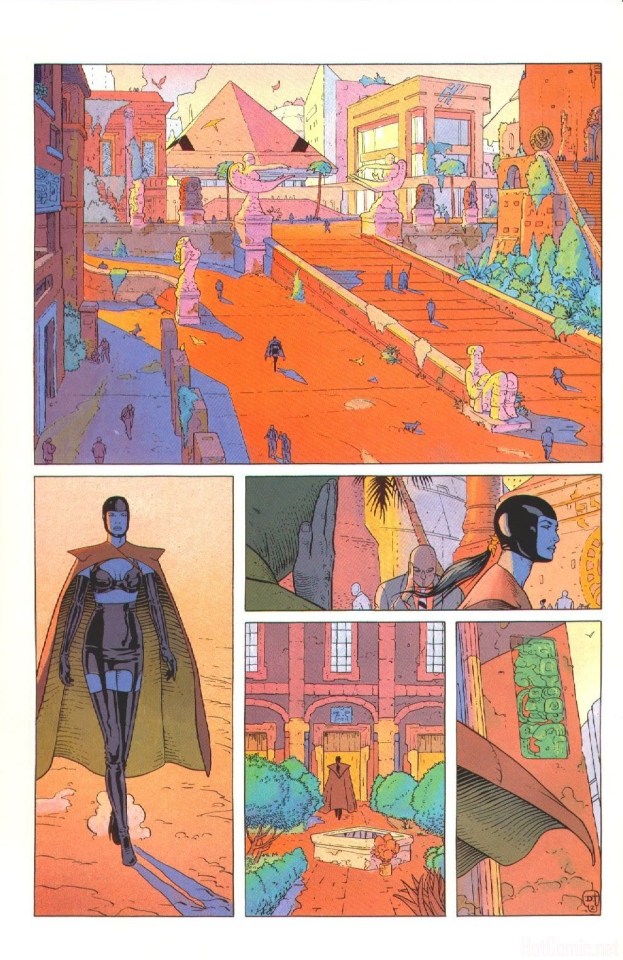

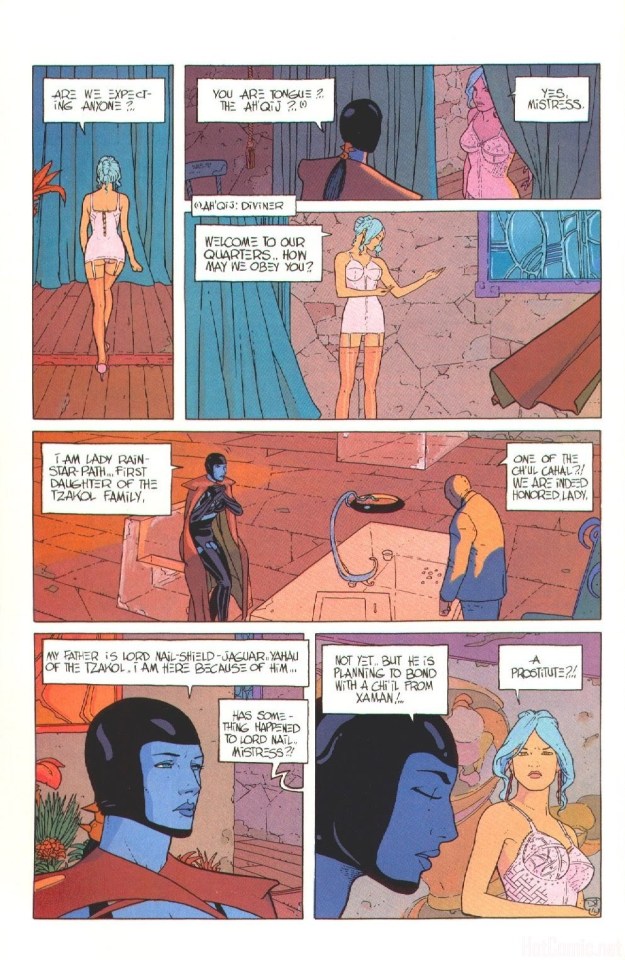

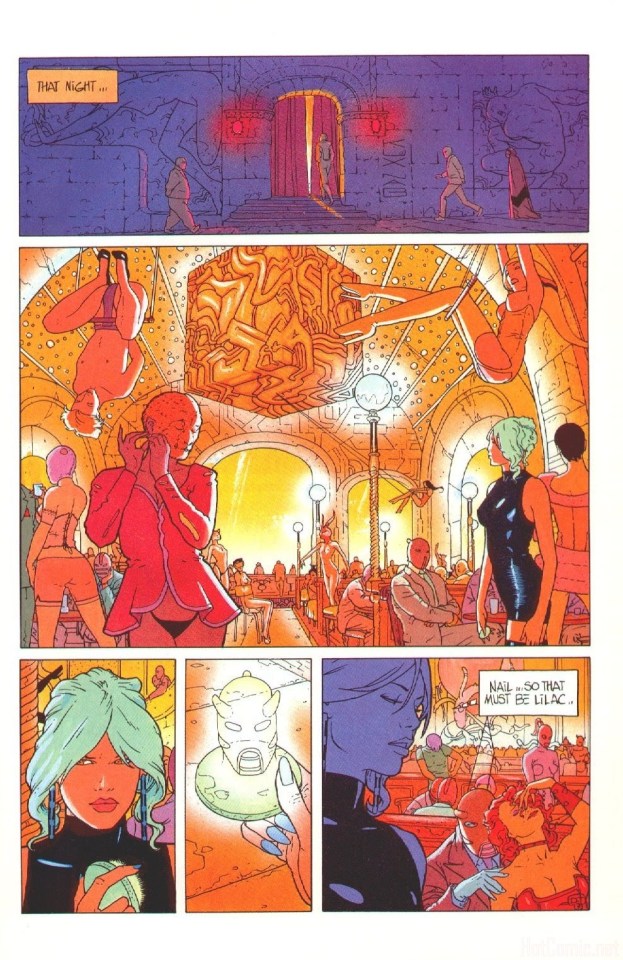

Here's a forgotten back issue gem. Dave Taylor does a perfect Moebius impression, and the story is a good read, kind of a cosmic detective tale.

Tongue • Lash #1: The Serpent's Tooth

by Randy Lofficier; Jean-Marc Lofficier;Dave Taylor;Scarlett Smulkowski

Dark Horse

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Superman and the Justice League by Tom Artis

#superman#justice league#green lantern#green arrow#zatanna#elongated man#flash#hawkgirl#black canary#tom artis#dc comics#modern age#randy lofficier#jean marc lofficier#robert fleming

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

JACK RUSSELL in DOCTOR STRANGE, SORCERER SUPREME (1988) #27 by DANN THOMAS, JEAN-MARC LOFFICIER, RANDY LOFFICIER, and ROY THOMAS

#marvel#doctor strange#werewolf by night#moon knight#comics#jack russell#stephen strange#marvel comics#wwbn#wbn#not my favorite origin of jacks father but this is a pretty good recap#i like the idea of his werewolf form getting fucked up by the ‘treatment’ and making him look more monstrous#but peak design is honestly the og / live action design

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animation Retrospective: The Real Ghostbusters

Something that's been on my mind -- the staff behind Star vs. the Forces of Evil have been getting away with quite a bit lately: a lot of violence, use of words like “death” and “kill”, and some honestly pretty psychologically dark and heavy stuff.

And thinking about all that got me remembering a cartoon that I used to watch when I was a kid in the late 1980s -- The Real Ghostbusters. I was -- and still am -- a huge fan of Ghostbusters. It is my favorite movie of all time. And as a kid, I watched The Real Ghostbusters -- the animated series based on the movie -- religiously.

Recently, I noticed that the first two seasons of the animated series were available on Netflix (as of this post, they still are!), which prompted me to briefly part from my previous topics here and write this post instead.

This will be a long discussion of my favorite three episodes from The Real Ghostbusters, during which I will also incorporate guidelines on three things: writing with internal logic, writing good dialogue, and using conflict to craft a compelling story. Despite the length of this post, I welcome you to read it in its entirety and provide feedback.

Before we start, though, I'd like to say that the writing isn't the only thing I like about The Real Ghostbusters, of course: I also love the voice acting, the character designs, the composition -- even the animation has moments of loveliness from time to time (though admittedly the series is mainly comprised of bog-standard '80s animation).

The writing, though, is where this series truly shines. Unlike Star vs. the Forces of Evil, which is storyboard-driven, The Real Ghostbusters is a script-driven series -- which makes a lot of sense for an animated series in the ‘80s. There wasn’t a whole lot of budget for animation (and the studios they had access to weren’t particularly remarkable), so the production staff focused on quality scripts. These three episodes in particular are emblematic of not only a well-made children's animated series but also just good, old-fashioned enjoyable storytelling for any audience. In my opinion, anyone who is interested in writing a script for an ensemble cast or in improving their dialogue could learn a thing or two from The Real Ghostbusters. Now -- let’s dive right in!

Episode 44: "The Thing in Mrs. Faversham's Attic" and Internal Logic

Yes, that J. Michael Straczynski. He was not only a writer for the series but the story editor as well, and the show's quality in its early run reflects that -- until ABC foolishly forced him out (but that's a story for another day).

This episode stands out because of its truly dark subject matter: it involves a haunting in a house caused by an entity -- heavily implied to be demonic in origin -- conjured up by a well-meaning father in dire need.

Looking back on it, I can't believe an episode like this got made in the 1980s. Many of you reading this now were not around for it, but the 1980s were a time of baseless widespread fear of rock music, Dungeon & Dragons, cults, and Satanism -- moral panics.

An episode like "The Thing in Mrs. Faversham's Attic" would have normally been nixed by ABC's Broadcast Standards and Practices, but this episode -- along with the two other episodes chosen for this post -- is part of the 65 episodes produced for syndication, meaning that they were subjected to looser restrictions than normal. As you'll see, it's because of those looser restrictions that we see darker themes, more action, and more adult-oriented dialogue. (Frankly, it's still amazing that these episodes got made at all.)

The episode, like many other early episodes of The Real Ghostbusters, has an undeniable internal logic acting as its driving force: the thing in Mrs. Faversham's attic has been confined there, and it's been making that place larger, day by day, year by year, nursing its grudge against the man who trapped it there. It takes on scary forms that are based on the sort of junk that people leave sitting around in attics -- it's both creatively inspired and eminently reasonable.

The Ghostbusters also figure all this out through detective work, a process we see in action: after an initial encounter with the thing, they return to the station to ask Mrs. Faversham some follow-up questions based on what they've learned, and Egon is the one who puts all the pieces together in a way that not only is consistent from what we've been shown but also is engaging and interesting to watch. The Ghostbusters aren't just occult-themed exterminators, after all -- they're paranormal investigators, and these three episodes really play up that aspect.

By building an episode around a sort of internal logic -- but not drawing too much attention to it -- and using those rules to bring the episode to the conclusion which follows, a writer can create a resolution which is immensely satisfying, even if the audience is not at first entirely sure why. (Indeed, one of the benefits of script-driven animation is that this internal logic can more easily remain consistent from episode to episode!)

"The Thing in Mrs. Faversham's Attic" also has some examples of excellently-written dialogue -- the dry, wisecracking humor so often associated with the Ghostbusters as well as a really quite menacing speech from the villain (especially menacing when coupled with its design):

Peter: (talking to himself) "'So, Peter, have a nice day?' 'Oh, yeah. Argued with a hat and a coat rack.' 'Really?' 'Yep, nothing new. How's about you?'"

Egon: Janine, why don't you show Mrs. Faversham the Containment Unit? I'm sure she'd find it fascinating. Janine: Of course. Come along, Mrs. Faversham. I'll show you where they figure out new ways to do stupid things.

Peter: Seven years of college, and I can never remember if it's positive to negative or positive to positive.

The Thing: So long have I awaited you, Faversham, here in my prison. Do you like it? I built it all myself. Every inch of it has the word hate written on it. That is how much I hate you for keeping me here. Only one thing has kept me from going mad: revenge! Revenge on the one who had imprisoned me! And now, here you are.

I won't spoil the climax of "The Thing in Mrs. Faversham's Attic" for you -- I want you to watch and enjoy all of these episodes for yourself -- but suffice it to say that it is genuinely terrifying, even to adult me.

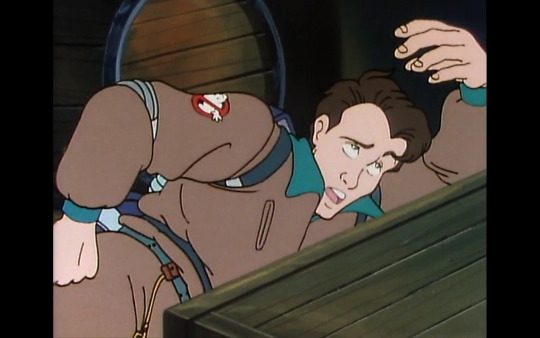

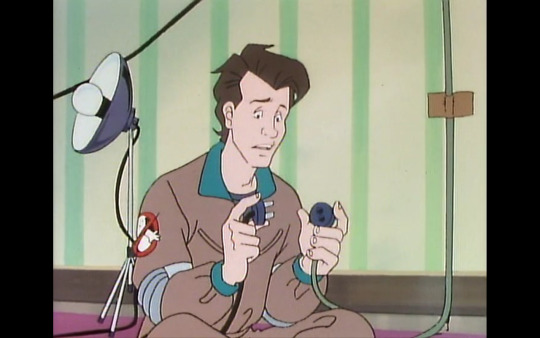

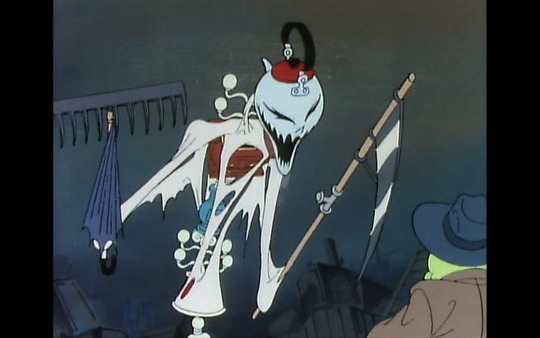

Episode 41: "The Collect Call of Cathulhu" and Dialogue

First things first: yes, it should be "Cthulhu" -- the person making the title card thought the name was misspelled (not to mention that Lovecraft's works were not quite yet in the public domain at the time of production). That being said, there's so much to appreciate in this episode; really, it's a love letter not only to Lovecraft but to science fiction writers everywhere. Like every other episode on this list, it also has some great dialogue:

[The Necronomicon has been stolen.] Kline: We must get it back! Otherwise, the city, perhaps even the world, is in grave peril! Peter: I don't see what all the fuss is about. It's just a book. Ray: And an atomic bomb is just a couple of rocks slammed together. Egon: This is the only English translation of the Necronomicon. If someone were to read the spells in it aloud, the results would be catastrophic.

Using this example, I’d like to show you that good dialogue ought to be doing several things at once:

Dialogue characterizes. We learn about characters through the things that they say, and their words reinforce what the audience already knows about them -- i.e., characters act according to what the writers have previously established. That creates a familiarity with the audience that allows them to get to know those characters. The audience can also learn new things about those characters or gain more awareness of traits that were previously only hinted at -- both of which should be in keeping with aspects that have already been established. (Though it's fine to surprise people, of course. People are indeed complicated and full of surprises.)

Dialogue captivates. Each character's diction -- their manner of speaking and word choice -- should engage the audience by being interesting while also fitting their character. In the example above, Ray is technically-oriented and knows Peter well, so he comes up with a rather surprising metaphor and presents it in a way that Peter can understand -- and the audience is meant to find the gallows humor wryly amusing. (Telling a joke is one way of keeping the audience's interest.) Egon, who is even more technically-oriented than Ray, reflects this with his unusual word choice, particularly in the use of the word “catastrophic”, which also foreshadows just how serious the threat will prove to be.

Dialogue establishes the setting. Characters should refer to the world they live in as if it is ordinary -- i.e., the audience learns something about the world through what the characters have to say about it. With the example above, for instance, we are able to infer not only that magic exists but that it's also extremely dangerous as well. Yet these facts are unremarkable to the characters; the writers assume we're smart enough to make inferences on our own, without them being explicitly spelled out for us.

Dialogue sets the tone and theme. Take another look at the example dialogue above; Peter's flippant remark (which is usual for him) is responded to with grim humor and grave warnings. In a less-serious episode of The Real Ghostbusters, Peter might simply have gotten away with such a remark, but in this episode, he is immediately corrected, establishing that, no, this is far more serious than a normal episode. In addition, the characters' discussion of the danger sets up the theme of magic being a dangerous force that few people can be trusted with.

Dialogue explains what's going on. In my opinion, this is the very last thing that dialogue ought to be doing. Once your dialogue does one or more of the previous things, only then can characters explain what's happening. The audience should learn something new about the immediate subject matter the characters are dealing with, or the plot should be advanced in some way. I don't believe in having expository dialogue simply for its own sake -- but if you think you can make it work in your writing, then go for it. (There are no hard-and-fast rules for writing, and people will like pretty much anything. I've seen it.)

Here's another example of dialogue from this episode:

[After running away.] Winston: Sometimes I really regret answering that ad you guys ran. Peter: Egon, what do you got? Egon: His power is completely off the scale. None of our equipment can even begin to stop him. We don't have a prayer. Peter: You're such a Pollyanna, Egon.

In addition to the dialogue, there are dark elements that got surprisingly overlooked by network censors: the Necronomicon, the cultists -- who, incredibly enough, literally chant "Iä! Iä! Cthulhu fhtagn!" -- the spellcasting, and the riskiness of everything the Ghostbusters end up doing. (I am truly boggled that such an animation was ever made in the Satanist-fearing 1980s.)

Indeed, in order to convey the danger of the threat that the Ghostbusters face, this episode incorporates a number of elements from the film -- which is itself is a serious treatment of a comedic idea -- to give the episode a cinematic treatment. For instance, the opening shot of the New York Public Library is directly lifted from the film, and much of the dialogue -- there's mention of Gozer -- refers back to moments from the film in new and interesting ways, all of it serving to underscore the danger the characters face.

If you watch this episode yourself, you'll see what I mean when I say that this entire episode is a love letter to science fiction writers of old.

Episode 43: "The Headless Motorcyclist" and Conflict

This is my absolute favorite episode, and I saved it for last. There's so much I could say about this episode: I love how cinematic it is; I love that it takes a fictional story from real life and adds some personal tragedy to it; I love the composition and how so many scenes take place on the dark and dirty streets of New York; I love the sophisticated and gritty, almost film noir themes in it (yes, really!); I love how Peter is depicted as the shameless womanizer he is (you know -- for kids!). It's just a perfect episode.

I could bore you for hours by talking about this episode, but I'd like to focus on the conflicts and how the problems these conflicts present offer opportunities for the story to move forward. First, a list of the central conflicts in the story, from beginning to end:

Bud vs. Kate

Peter vs. Bud

Officer Frump vs. Peter

The Headless Ghost vs. Kate (and Her Family)

Officer Frump vs. The Ghostbusters

The Ghostbusters vs. The Headless Ghost

The episode starts with Bud and Kate having an argument at a party. Peter initially gets involved because he's attracted to Kate, but after he overhears the argument and Bud starts to hurt Kate, he steps in, and they almost fight. Bud leaves the party. After Bud leaves, he's followed by the Headless Ghost, who destroys his car. This chance encounter provides the impetus for Bud to contact the police, who naturally assume Peter had something to do with it:

[Officer Frump shows the Ghostbusters photographs of the burnt-out car.] Officer Frump: And the guy was lucky not to end up the blue plate special at Bob's Barbecue Hut. Peter: Okay. So you want us to investigate this motorcycle spook, right? Officer Frump: Wrong. Peter: Wrong? Officer Frump: (taking out a photograph of Bud) Know this guy? Peter: Yeah, sure. I met him last night. We had an argument -- Officer Frump: That's the guy who was almost barbecued. Peter: (quietly) Ohhhh.

The small conflict between Bud and Peter escalates into a larger one: Peter needs to prove his innocence, or he'll be going to jail for a crime he didn't commit. Because the Ghostbusters are scientists and paranormal investigators, they employ logical thinking in order to solve their problems. Their first idea is to retrace Bud's steps using the same car he drove, which works. After gaining an idea about the ghost, they contact Kate to find out more about the ghost, where they learn about her family's history.

It's then that the Ghostbusters realize the true scope of the conflict taking place and decide to do something about it. By this point, as more information is revealed and multiple parties become involved, further pressure is put on the Ghostbusters -- they need to figure this out, or else they'll all be going to jail -- which ratchets up the dramatic tension.

This is good writing! Start with a small conflict, then raise the stakes. As the characters react to the raised stakes, the situation continues to escalate, propelled by a kind of logic (sometimes a horrible one in particularly violent stories), until a final confrontation becomes impossible to avoid. In “The Headless Motorcyclist”, the Ghostbusters go about their problem-solving methodically; not only is that entirely in keeping with their scientifically-minded characters -- it's also interesting for the audience, especially when their plan is at last revealed.

The dialogue underscores the adult nature of the conflict taking place; read this dialogue and try to remember that this is a kid's show:

[The Ghostbusters are working on something.] Janine: (off-screen) You can't just barge in here like this! Officer Frump: Well, what have we here? Not preparing to let some ghosts loose, are we? By the way, I found that this Bud character is an insurance investigator -- and you were selling ghost insurance at the party. What a coincidence, eh?

I told you that this episode has an almost film noir-ish feel to it, and it's definitely dialogue in scenes like this that help give this episode that extra punch it needs. Even the ending of the episode is some kind of cinematic experience -- just look at the expression on Kate's face and the way the camera pans in:

In just a few seconds, you can see all those years of hate and fear of being followed and tortured by the Headless Ghost. We feel her pain in those moments. And yet -- and yet all we're truly looking at in these moments is a bit of paint on a plastic film. To me, that is the epitome of the true magic of animation.

What Do You Think?

If you have Netflix, I highly recommend watching The Real Ghostbusters -- and, in particular, the episodes I mentioned above. Please, please try giving the series a shot. I’ve tried to say as little as possible about the endings -- I think that if you watch these episodes, you’ll be pleasantly surprised, and you may find that you like other episodes as well! Fan favorites include "The Boogieman Cometh", "When Halloween Was Forever", "Ragnarok and Roll", and "Cold Cash and Hot Water".

If nothing else, here are the main ideas in this post I want you to come away with:

The very last thing that dialogue should do is explain what's going on. It should always serve to give life to characters first, then the world, and so on until finally getting to the narrative.

All of your characters in an ensemble cast can have something in common -- a shared dry, sardonic wit, for example -- and yet still be distinct based on other characteristics, such as temperament, word choice, and outlook.

Animation for children doesn't have to be vacuous or insipid. It can be wry, complex, and dark.

Feel free to ignore everything I’ve just told you. I like to give stylistic guidelines on how to write well -- but those are merely my opinions on what good writing is. That is a style. Ultimately, there are no hard-and-fast rules for writing. If you like writing long paragraphs of internal monologue with no line breaks or punctuation, and you think your style works for what you're trying to accomplish, then go for it. There seems to be an audience for just about everything these days, so don’t be afraid to forge your own path.

Thank you for reading this post! I hope you enjoyed it. Feel free to submit any questions you may have, whether on Star vs. the Forces of Evil or The Real Ghostbusters or whatever else is on your mind. If you have sent me questions previously, don't worry; I will answer them soon. If you’d like to chat with me, you can also join me in IRC at the link in my about page, and you can check here for a list of my previous analyses and theories. Take care of yourselves!

#the real ghostbusters#real ghostbusters#dialogue#writing#j michael straczynski#michael reaves#randy lofficier

35 notes

·

View notes